TOBIAS A. UNRUH AND THE LOW GERMAN MENNONITES OF VOLHYNIA

von Rod Ratzlaff - Mail: ratz01a@gmail.com - Website: https://ratz01a.wixsite.com/groningenoldflemish / Blog: http://ratzlaffhistory.blogspot.com

Mit Google Chrome kann man den Text Übersetzen lassen. Falls sich jemand findet der diesen Text ins deutsche übersetzen möchte, würden wir den hier reinstellen.

TOBIAS A. UNRUH AND THE LOW GERMAN MENNONITES OF VOLHYNIA

(Version 11.8.19)

Based on a presentation given at Freeman, South Dakota

© Rodney D. Ratzlaff, November 2019. - ratz01a@gmail.com

All of my paternal grandfather’s ancestors came from Volhynia and this ancestry spurred within me a keen fascination for study of the history of the Low German Mennonites living there. My great great great grandmother, Anna [Koehn] Voth, Ratzlaff, was born in 1824, probably in the village of Antonowka. She, along with her second husband Peter Ratzlaff and their children came to USA in 1874 aboard the SS Vaderland. My great great grandfather, Jacob Ratzlaff, was born in 1843 in Antonowka. He, along with his wife Anna [Voth] (daughter to the above Anna [Koehn], and his children Henry (with family), Bernard (and wife), Adam, Helena, and John, came to USA in 1893 aboard the SS Polaria. My great grandfather Andreas Ratzlaff was born in Lilewa in 1869. He came to USA in 1907 aboard the SS Weimar. He traveled with his wife, Susanna [Wedel] and their young children Marie, Karoline, Katherine, John, Florentine, and Susanna. Also traveling with them were Susanna [Wedel]’s parents (my great-grandparents) Peter Jacob and Katherine [Nickel] Wedel. The legend is that Andreas was the last Mennonite Schultze of Lilewa. He and his family came to USA so late because Andreas, as Schultze, felt it was his duty to be the last one to leave the village[1].

The following is a very brief survey of the history of the Low German Mennonites of Volhynia. Of course, we could delve into much more detail of almost every point found below but the objective here is simply to give an overview.

Low German Volhynian research is challenging in that records are extremely hard to find. The isolated nature, as well as turbulent history, of Volhynia has resulted in destruction or loss of records. Also, many Volhynians in Kansas converted to the Holdeman sect and this makes research via the Mennonite church difficult. Today, Ukrainian archives are not easy to deal with, for many reasons. Due to these challenges, Volhynian research has been neglected. But since it has been neglected, there are still a lot of exciting discoveries to be made.

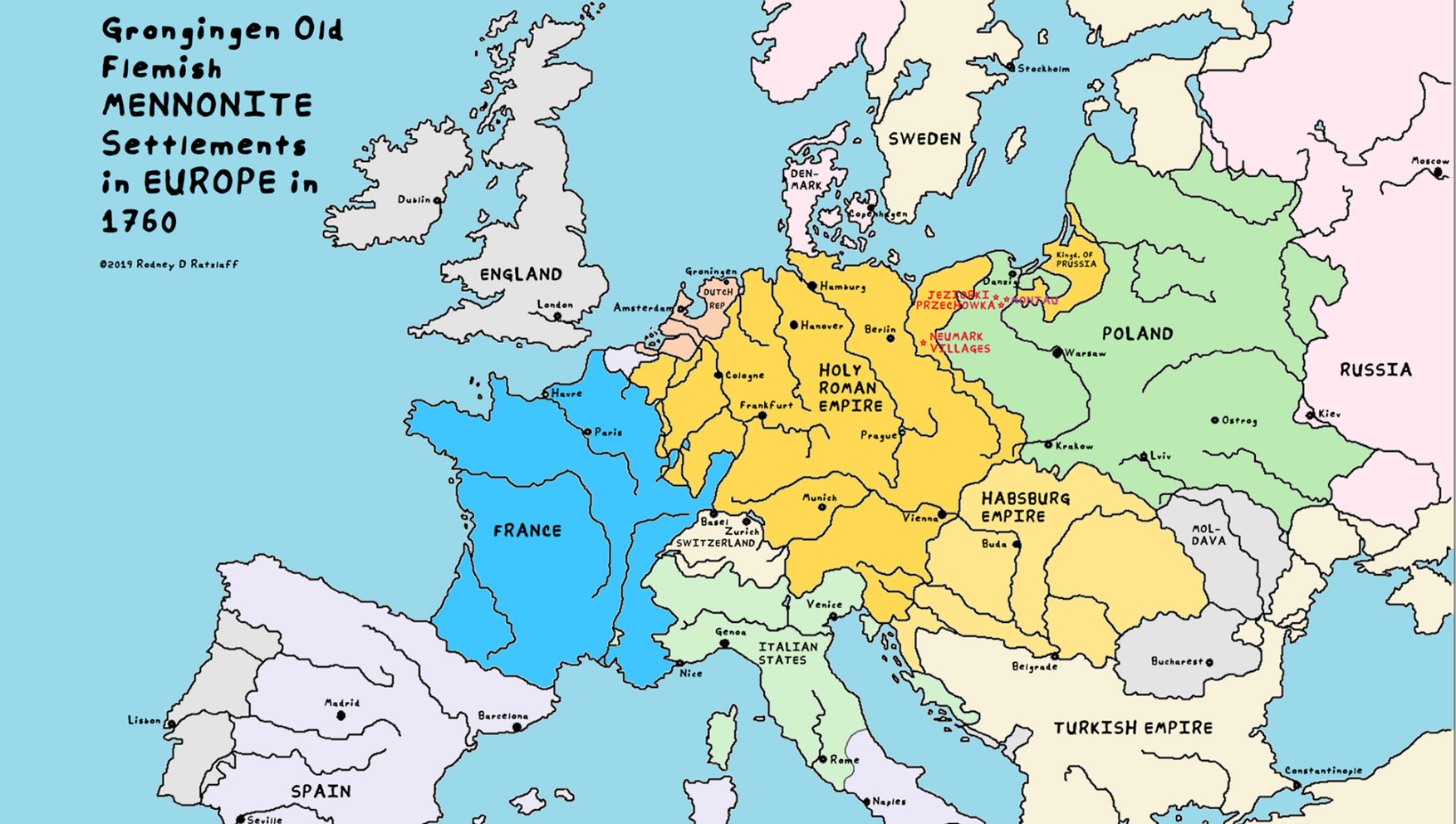

The Anabaptists developed independently in the early 16th Century, both in Switzerland and in the Dutch Lowlands. Those in the Dutch Lowlands largely spoke the Low German language and an early leader among these was Menno Simons[2]. Almost immediately these Low German “Mennists” or “Mennonites” began to be persecuted by their Roman Catholic overlords and very soon began looking to migrate to a new home. By the mid-1500s they had already begun to colonize areas along the northern Vistula River, in the Kingdom of Poland, in areas known as Royal and Ducal Prussia[3].

The Low German Mennonites developed along the Vistula River and enjoyed a level of religious liberty and autonomy under the Polish kings of the 16th to 18th Centuries. Here along the Vistula River they established fourteen congregations[4], some of which were quite large. They drained the swamps along the large River and developed sophisticated agricultural systems which helped stimulate the economy of the Polish Kingdom[5]. These folks all spoke Low German on a day-to-day basis although they used either Dutch or High German in church[6].

In these days, along the Vistula River, the Mennonites’ religion flourished. Two different sects emerged – the Flemish and the Frisians. Just like today in the greater Mennonite Church there are different sects such as Conference USA, Mennonite Brethren, Old Mennonite, or Amish, etc., back then there were the Flemish and the Frisians. That’s actually over-simplified; there were actually Hard Frisians and Soft Frisians, Old Flemish, Young Flemish, Danzig Old Flemish, and even several others[7], but the primary division was Flemish and Frisian. The following will concentrate on one of the Flemish factions; the Groningen Old Flemish.

There was only one Groningen Old Flemish congregation in the entire area here along the Vistula River[8]. It was actually one of the smaller congregations along the river valley but it was the most strict and most conservative of them all; this was the congregation called Przechowka and it was located about 70 miles south of the coast of the Baltic Sea. Przechowka developed by the mid-1600s and congregants lived in a handful of nearby villages as well as the village of Przechowka itself[9]. Over the years, villagers expanded and new congregations were formed. In 1727 a congregation was established at Jeziorki, about 15 miles northwest from Przechowka, and in 1764 a second congregation was established in villages in Prussian Brandenburg in an area known as the Neumark. The Neumark villages were Brenkenhoffswalde, Franzthal, and Neu-Dessau. Both of these daughter congregations, Jeziorki and the Neumark villages, maintained close ties with the mother congregation at Przechowka[10]. Last names common to these congregations included Becker, Buller, Cornels, Decker, Dirks, Frey, Funk, Isaac, Jantz, Koehn, Nachtigal, Pankratz, Ratzlaff, Richert, Schmidt, Sparling, Unrau, Voth, and Wedel[11].

As Przechowka was expanding, significant changes were developing in the environment of the Vistula valley which would bring many of the Low German Mennonites to leave the Kingdom of Poland. Many would leave for the Empire of Russia. Among these developments were the Partitions of Poland and Empress Catherine’s Manifesto.

In Poland, political turmoil beset the kingdom and by the mid-18th Century, Poland was in trouble. Prussia, Russia, and Austria, in 1772, 1793, and 1795, partitioned the lands of Poland among themselves and afterwards Poland ceased to exist as an independent political entity. Most of Royal (West) Prussia, where the bulk of the Low German Mennonites lived, was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia – thereafter becoming West Prussia. The pacifist Mennonites quickly found themselves at odds with the militaristic Prussians and it wasn’t long before these folks began looking for a new home.

In 1763, the Russian Empress, Catherine, issued a manifesto inviting German colonists to move into areas of Russia newly acquired from the Turkish and Polish kingdoms. Catherine knew the Germans were excellent farmers and was eager for her new lands to be developed into productive farmland.

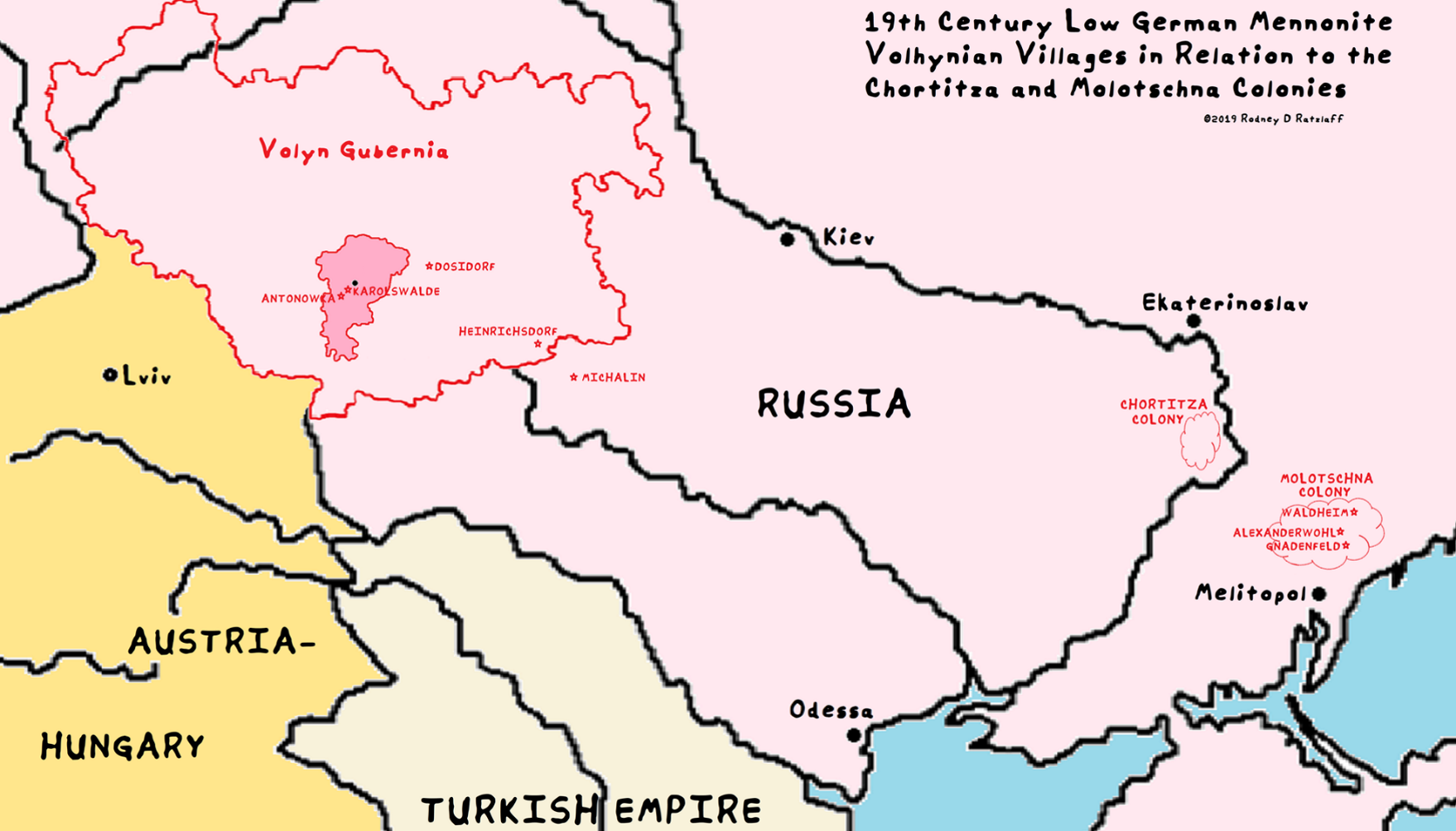

So then, after the Partitions of Poland, this is what Europe looked like for most of the 19th Century. The Vistula homelands of the Low German Mennonites were now part of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was on its way to becoming the most powerful German State. A great many of the Low German Mennonites from the Vistula Delta and Valley, having lost their religious freedoms, began moving into Imperial Russian territory. Very large colonies were established in the south such as the Chortitza and Molotschna colonies[12]. These colonies became very prosperous and were home to several thousand Low German Mennonites. But there was another area of Low German Mennonite colonization in Russia which is not at all well-known. This was area where Mennonites did not become prosperous but was in fact home to the very first Mennonite settlement in Russia; this area was known as Volhynia.

Volhynia (or Volyn in Polish, Ukrainian, or Russian, Wolhynien in German) is a geographical area located in central eastern Europe which lies within the traditional borders of Ukraine. It was located near the western border of the Empire of Russia in areas that before the 19th Century had been dominated by Polish culture.

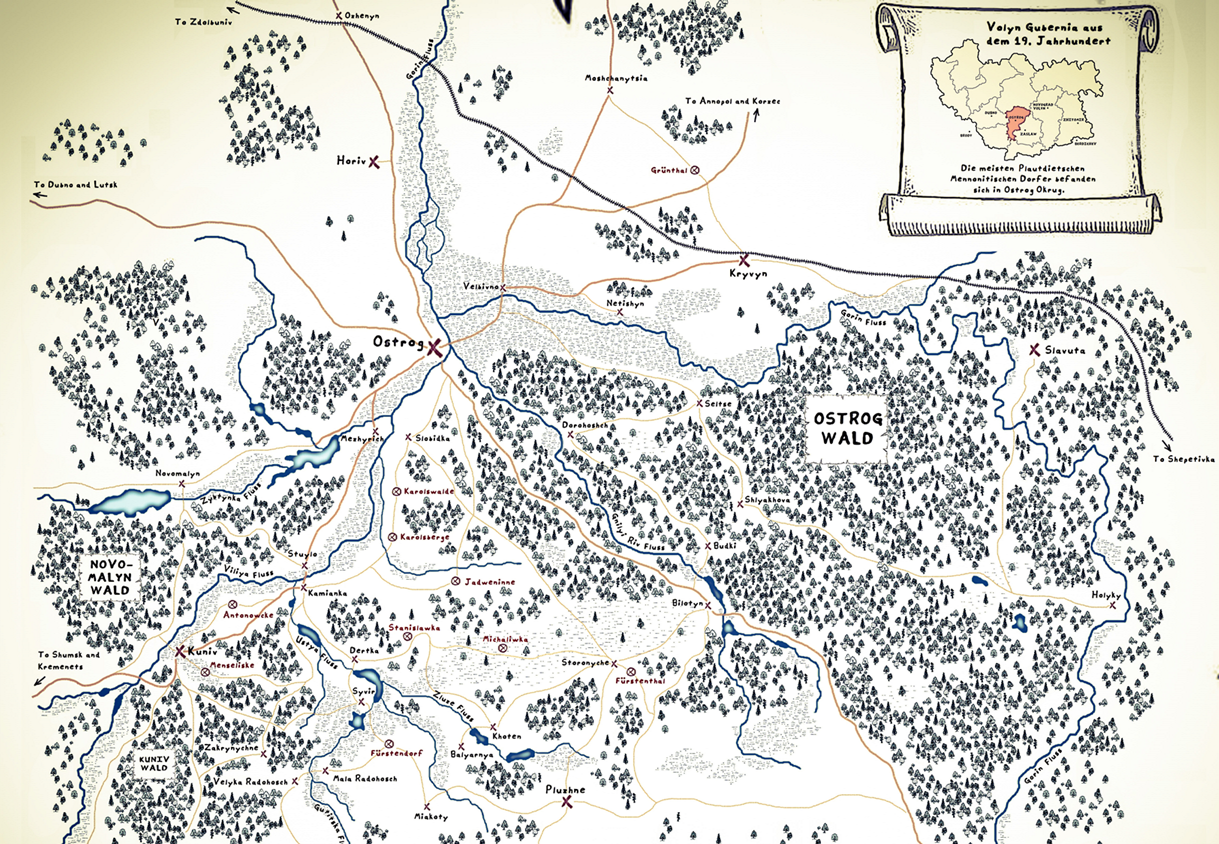

Volhynia, or Volyn Gubernia as it was known during the Russian Imperial period, was an area of western Ukraine about half the size of the State of Iowa[13]. Most of the Low German Mennonites lived near the town of Ostrog, which was located centrally in Volhynia. The area is geographically isolated and in the 19th Century was very difficult to reach via road, rail, or river. As such, it was a cultural and technological backwater[14].

Poles and Ukrainians have historically regarded Volyn as a border-lands territory. It lies where Poland, Ukraine, Russia, and Belorussia, all meet. Throughout history, this area has been alternately controlled by Russia, Poland or Ukraine. This area was home to a wide variety of ethnic groups, languages, and religions. In the 19th Century there were Ukrainians, Poles, Russians, Germans, Czechs, as well as Gypsies and Turks living here[15].

Different religious groups included Jews, Muslims, Orthodox, Catholics, Lutherans, Baptists, and Mennonites[16]. With such a wide variety of people came many languages. As a result, many place names in the area have different names in the different languages and this can make research tricky[17]. During the 19th Century, Ukrainians (who were Orthodox) were by far the largest ethnic group, followed by Jews and then Catholic Poles[18]. Very few ethnic Russians lived in the area in the 19th Century; those who did were mostly government officials in Ostrog or soldiers stationed at the nearby military garrison[19].

Of course, all these people didn’t always get along. For instance, generally speaking, the Poles hated the Russians, the Germans distrusted the Poles, and the Ukrainians felt victimized by everyone. The Jews and the Muslims hated one another and the Orthodox were at odds with the Catholics. And everyone looked a little sideways at the Mennonites. The Russian government only recognized the Orthodox and the Lutherans as official religious groups. These different ethnic groups didn’t always live peaceably with one another and occasionally violence did break out in the area[20].

Various Mennonite settlements were established in Volhynia over the course of the 19thCentury. The very first Mennonite village to be established in Volhynia (actually it was just outside the border of Volhynia) was the village called Michalin[21]. It was settled in 1791 and the church there was organized in 1811. The history of Michalin is a little hazy but it appears as if it was settled by Old Flemish Mennonites coming from the Przechowka villages along the Vistula River. After several years, these were joined by Frisian Mennonites coming from villages of the Montau congregation. Late in the 18th Century, a dispute arose between the Mennonites and the landlord of Michalin and the Old Flemish villagers moved elsewhere in Volhynia[22]. Those who stayed, mostly Frisians, eventually thrived at Michalin[23]. Surnames which were common in Michalin included Ewert, Harms, Klassen, Kliewer, Nickel, Schmidt, Schroeder, and Voth.[24]

Slightly later, Mennonites began settling on scattered estates or villages in northern and western Volhynia near the large towns of Lutsk and Dubno. These settlers generally did not have beneficial land contracts and many of these settlements didn’t last too long. Most of these settlers were Old Flemish. These settlements included areas near Wolla, Sofiowka and Josefin[25].

The primary Low German Mennonite villages in Volhynia were Karolswalde and Antonowka. These villages were established in 1801 and 1804, respectively, by Old Flemish Mennonites coming mainly from Przechowka and closely associated villages[26] as well as from Michalin[27]. A list of the most common surnames in these villages in Volhynia is very similar to the earlier list of surnames from Przechowka: Becker, Buller, Decker, Dirks, Jantz, Koehn, Nachtigal, Penner, Ratzlaff, Richert, Schmidt, Unruh, Voth, and Wedel. Some Frisian names which probably came from Michalin were also added including Boese, Eck, Ewert, Nickel, Siebert, and Schultz. Some German names such as Litke and Schartner[28] were also added.

One final wave of settlement in Volhynia resulted in the establishment of the village of Heinrichsdorf. Old Flemish settlers coming from the Neumark villages established the village of Waldheim in the Molotschna Colony in 1835. These settlers were joined by many of the Mennonites living in the scattered settlements in northern and western Volhynia. After several years in the Molotschna, however, the cultural difference was found to be too significant and many who came from the scattered Volhynian settlements left the Molotschna, returned to Volhynia, and formed the village of Heinrichsdorf in 1848[29].

Low German Mennonite villages in Ostrog County, about 1874, ©Rodney D. Ratzlaff, 2019.

So then, with the exception of Heinrichsdorf, the great majority of Low German Mennonites in Volhynia lived in Ostrog County in the villages of Karolswalde and Antonowka. In time, the population of these 2 villages grew and new villages were established.

- Karolsberge was established in 1828[30].

- Jadwinin was established in 1857[31],

- Grüntal, Fürstental, and Fürstendorf were all established between 1860 and 1870[32].

- Menziliski was established sometime shortly before 1874[33].

Ostrog County was the district which was home to most Low German Mennonites in Volhynia. Ostrog itself was an ancient city with a well-developed culture. One of the oldest universities in eastern Europe was located there and the first printing of a Bible in a Slavonic language occurred in the town in the late 16th Century. In the 19th Century, the town became a hub for Jewish scholarship. Ruins of an ancient storybook castle were located on the hill of the town, complete with a moat and a drawbridge and legends of princesses trapped in the tower. The Karolswalde villagers could doubtless see this castle as they toiled in their fields. Also nearby was the influential Mezerich monastery, an eastern Orthodox monastery which had been established in the 16th Century[34].

The Low German villages were established and leased to the Mennonites by local landowners. These Mennonite settlers did not benefit from many of the advantages offered by Empress Catherine’s 1763 Manifesto[35].

These Volhynian Low German villages were settled according to Dutch Law (as they had been in Polish lands even in the Vistula Delta and Valley) and the inhabitants were oftentimes referred to by locals as Hollanders[36]. Originally, Dutch Law villages were settled by ethnic Dutch farmers on Polish lands. However, by the 19th Century this ethnic connection had fallen away and the term Hollander was simply a description of the law by which the village was settled. Characteristics of Dutch Law villages included protestant villagers who were mostly farmers. The village land contract always provided for a level of autonomy and allowed the villagers to set up their own school and administration. Finally, the contract would provide a certain acreage of land which would be divided, at the villagers’ discretion, among themselves according to need or ability. It was literally a “one for all, all for one” situation for the villagers. Land contracts were typically 20- or 30-year terms[37]. This use of the term Hollander gave rise to the myth that these Volhynian settlers had come directly from Holland. In reality, as we have already discussed, they came to Volhynia from Polish Prussia[38]. In reality, it’s highly unlikely that any of them came directly from Holland.

When the Low Germans moved into Volhynia from Polish Prussia, they brought their style of house along with them. This form of house was a descendant of the type known as the Dutch langhaus. This type of house was a house-stable-barn all contained in one structure[39]. In time, the Mennonites added a Russian-style oven to warm the house portion. Houses in Volhynia were built with logs from the forest and had thatched roofs. The Karolswalde villagers were generally a little more prosperous and the houses there had wooden floors and stone foundations. Villagers in Antonowka were generally poorer and even into the 20th Century the houses in this village still had dirt floors and perhaps only had foundation stones under doors or windows[40].

Villages were laid out with staggered houses on one side of the road. Long, narrow fields then stretched out from each house[41]. On this old Russian map three of the Mennonite villages can be seen: Antonowka (Антоновка), Karolswalde (Карлс-вальдъ), and Jadwanin (Яавинина). Karolswalde was situated in a generally north-west orientation. Houses were built on the west side of the road and fields stretched out from each house, westwards, towards the Klinovets Stream. Both Antonowka and Jawanin were laid out in an east-west orientation, with houses on the north side of the road. Fields then stretched out to the north from each yard; in Antonowka they reached towards the Viliya River and in Jadwanin, towards the Klinovets Stream.

In the early 19th century the area was lightly populated and land allotments were the equivalent of 40-50 acres per farmer. Later, as population grew, acreage could be as little as 5 or 10 acres per farmer[42]. Also, as time passed, not everyone was lucky enough to acquire their own land or house and some houses became inhabited by more than one family.

The soil in this area of Volhynia was not very good for growing crops; it was high in sand and clay content[43]. When the Mennonites arrived in the area in the very early 1800s, field areas had to be cleared from the large native forests in order to sew crops. Rye was far and away the most important grain crop in the 19th Century followed by wheat, oats, and barley[44].

Raising livestock was actually more lucrative than growing crops. Pigs, cattle, chickens, ducks, etc, were commonly raised[45]. It was also very popular for Mennonites to raise honeybees, in fact, the art of apiculture was widely practiced throughout Polish, Ukrainian, and Russian lands.

Most Low German Mennonite houses contained spinning wheels and looms to spin flax or hemp into linen. This was a tradition brought over from the Vistula River valley in Poland. Both my great great grandfather Ratzlaff and my great grandfather Ratzlaff listed weaver as their occupation[46].

Many Mennonites also worked at cutting wood in the nearby forests. The vast forests of Volhynia were recognized as a very valuable resource. Government Foresters patrolled the woods and the unauthorized cutting of timber was strictly prohibited and swiftly punished by the local police. However, there were opportunities to cut timber in the Ostrog, Kuniv, or Novomalin Forests[47].

Mennonites had to come up with other vocations to make enough money to pay their rent. Germans in general were recognized as expert agriculturalists but those without land had to work elsewhere. Around the turn of the century in Ostrog town were 10 tanneries, 3 soap-makers, 2 candle-makers, and 2 tile factories which provided jobs[48].

Other manufactories in the nearby area included a distillery in Miakoty, a stone quarry in Kamenka, a lumber mill in Zakrenicze, a pottery/tile factory in Bialotyn, clay mines in Wielbowno, carriage factories in Dorohoszcza and Antonowka, and a barrel factory in Balary[49]. People also fished in the many streams in the area and plenty of folks worked as day laborers on nearby estates such as those centered at Mezeritch, Pluzhne, and Krivin[50]. Inns in both Karolswalde and Antonowka provided a few more jobs[51]. Finally, it was not unheard of to rent out children to more prosperous neighbors or even to relatives in the Molotschna Colony, 500 miles away[52].

The great majority of Low German Mennonites who had come to Russia went to the colonies in southeast Ukraine such as the Chortitza or Molotschna. These colonies were some 4-500 miles southeast from Volhynia. These large Mennonite colonies were much more prosperous than Volhynia and the Mennonites’ lives developed in profoundly different ways.

For one, the southern colonies were fairly isolated from local Ukrainians or Russians. On the other hand, the Low Germans in Volhynia literally lived among the locals and had to interact with them on a daily basis. Thus, the Volhynians’ culture was influenced by local Ukrainians, Poles and Jews, in ways the southern colonists’ culture was not. Years later, upon arrival in Kansas, Molotschna Mennonites would accuse Volhynian Mennonites of being lazy and uneducated – they had supposedly been influenced by Ukrainians and Russians and Poles[53].

The southern colonies were located in the Ukrainian Black Earth area which has extremely fertile soil. This fertile soil provided the basis which supported the prosperity of the southern Mennonites. Volhynia is just on the northern edge of this Black Earth region and the soil is not nearly so fertile. Since they didn’t till the land much, the Volhynians did not develop sophisticated agricultural methods like those in the southern colonies did. This proved to be a major handicap for them when they moved away from Russia.

The Chortitza and Molotschna Mennonites owned their own farms while the Volhynians were largely forced to rent from landowning nobles. Generally speaking, Chortitza and Molotschna Mennonites also enjoyed taxation benefits that the Volhynians did not.

The prosperity of the Chortitza and Molotschna Mennonites provided them the opportunity to develop secondary schools, homes for the elderly, and even industrial factories. They kept good historical records, developed specialty cuisine and church life flourished. Conversely, the Mennonites in Volhynia were simply worried about how to put food in their stomachs and couldn’t worry about more sophisticated things[54].

As Groningen Old Flemish congregations, Karolswalde and Antonowka maintained contact with the other Groningen Old Flemish congregations in the Molotschna Colony which were all daughter communities to Prechowka. The village of Alexanderwohl was actually the successor to Przechowka. Another village, Gnadenfeld, was the successor to the Neumark villages[55]. As an example of the connection between Volhynia and Alexanderwohl we have this story: Johann Schartner was a minister in Karolswalde prior to the great Mennonite immigration in 1874 which saw most Volhynians, as well as most Alexanderwohlers, move to USA. After 1874 Schartner moved to the Molotschna and became the new elder of Old Alexanderwohl. He was ordained there by the elder at Gnadenfeld. After he became the elder at Old Alexanderwohl he continued to serve the Volhynian villages, regularly traveling back to complete baptism or wedding ceremonies[56].

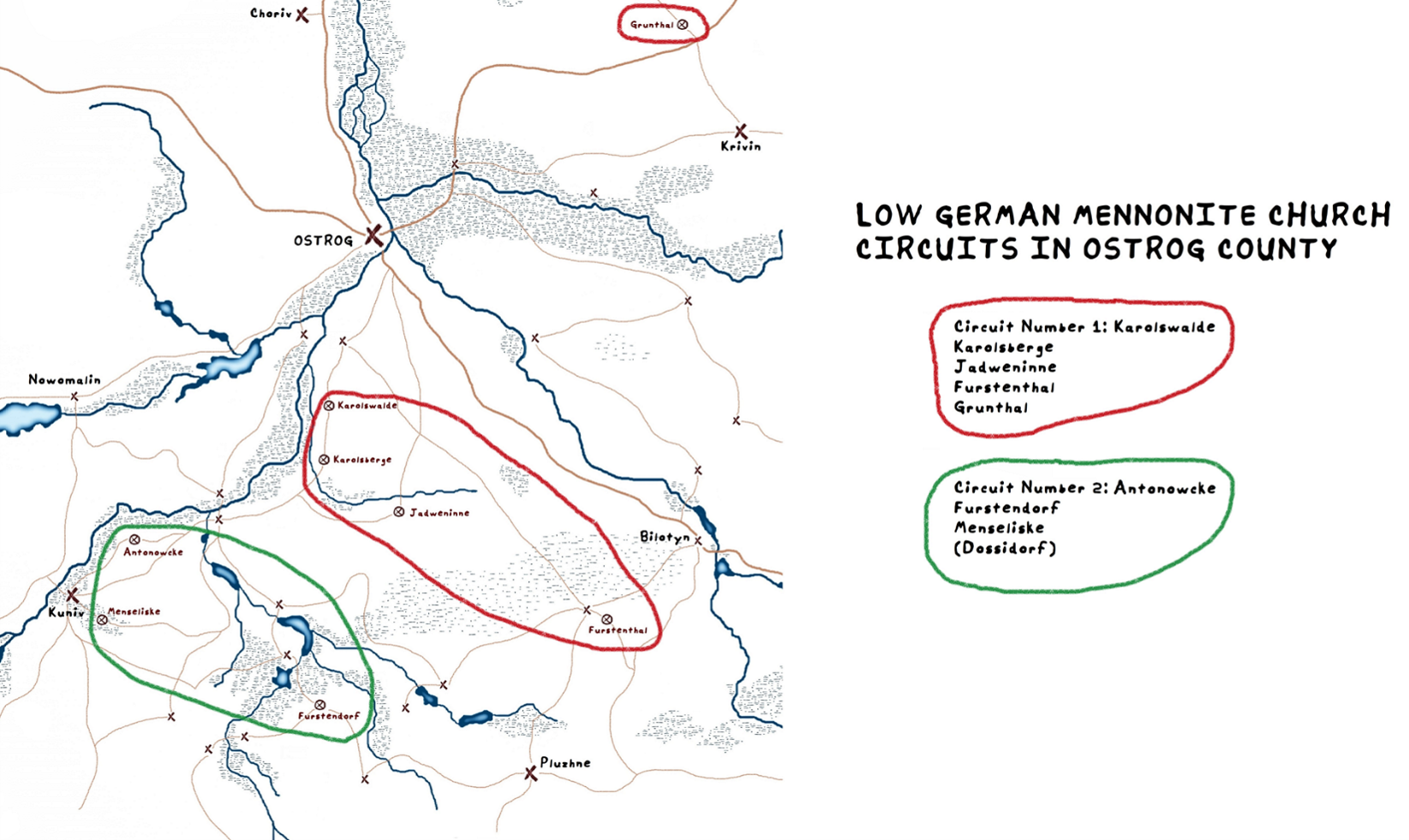

The Low German Mennonites in Ostrog County divided themselves into two parishes, under one elder. In the very early days, Karolswalde and Antonovka Martin Abram Voth, original settler at Karolswalde, was the elder of the community. Then in 1817, Benjamin Dirks was ordained as the second elder in Karolswalde. He served as elder from 1817-1853. Elder Dirks died in 1853 and was then succeeded by Tobias A. Unruh[57].

The Karolswalde Parish included the villages of Fürstenthal, Grünthal, Jadwanin, and Karolsberge. The Antonowka Parish included Antonowka, Fürstendorf and Mensiliski[58].

Also under the Karolswalde elder’s umbrella was the village of Heinrichsdorf which was located about 80 miles to the southeast. The village of Michalin had its own elder since at this time all these communities still clung to the Old Flemish/Frisian division. The Karolswalde congregations were Old Flemish while Michalin was Frisian. The first elder in Michalin was David Siebrant who served from 1816-1851. He was succeeded by elder Johann Schroeder[59].

Elder Tobias Unruh was born 28 May 1819. This very year marks his 200th birthday even though his birthday was probably marked according to the Old-Style Gregorian calendar. His wife was Helena Thomas who was born in 1821. Both the elder and his wife were probably born in Karolswalde and their ancestors came from Przechowka villages, either Jeziorki or the Neumark villages.

Unruh was ordained as elder of the Low German Mennonite church in Volhynia in September, 1853, by Johan Schroeder, elder at Michalin[60]. It was Elder Unruh who supported the Low German Volhynian Mennonites through their last years in the Russian Empire and guided the majority of them to North America in 1874 and 1875.

The notion to emigrate from Russia was spurred by anti-German laws passed beginning in the 1860s by the Imperial Russian government. These anti-German laws were part of an attempt by the government to Russify the population. When German colonists – both Mennonites as well as Lutherans and Baptists and Catholics – had been invited into the Empire in the late 18th Century, many of them had been granted special privileges and benefits which divided them from the local Ukrainian population. These advantages helped them, in many cases, to become more prosperous and by the mid-19th Century, this was the source of animosity between the colonists and the local Ukrainians.

Beginning in the 1860s, new laws were passed including some which:

- Limited Germans’ ability to purchase land and curtailed Germans’ administration of their own schools and villages.

- Additional new laws mandated universal taxation and military service for all inhabitants of the Empire, including German colonists.

- Finally, village schools were required to instruct the Russian language and German village names were required to revert to Slavic equivalents[61].

It was after this time that some of the Low German Mennonite villages acquired their Slavic names: for instance, Karolswalde became Holendry Slobodka; Fürstenthal became Kustarna, Fürstendorf became Lilewa, and Grüntal became Moschanovka[62].

These laws, and other like them, were beyond what many Russian Mennonites were prepared to accept. Thus, in 1873, Mennonites in Imperial Russia sent 12 Delegates to travel to North America to scout locations for a new home. Delegates were sent from the Molotschna and Bergthal Colonies, from the Swiss Volhynians, from West Prussia, from the Kleine Gemeinde, and from the Hutterites. Finally, from the Low German Volhynian communities, Elder Tobias Unruh was also sent[63]. The task before these delegates was to go to North America and find suitable locations for a new home.

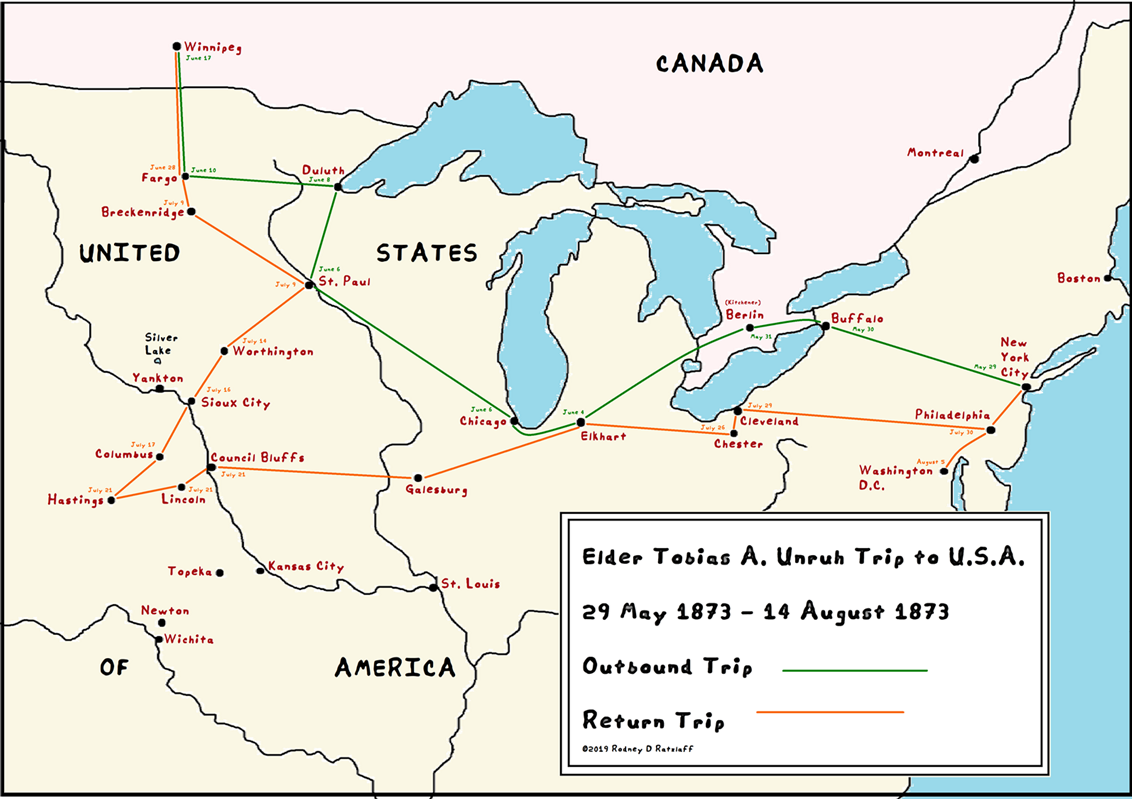

The delegates landed in New York City and the preceding map illustrates Elder Unruh’s general route. He, along with some of the other delegates toured North America starting from New York City, through Ontario (Kitchener, home to Jacob Schantz and Cornelius Jansen), then to Elkhart (home to John Funk) and Chicago, to St. Paul, Duluth, and Fargo, up to Winnipeg in Canada, then back to Fargo and St. Paul, through Sioux City and down into Nebraska. At no point did he enter Kansas. From Nebraska, he returned to Elkhart, made a stop to visit the minister John Holdeman in Ohio, then came back to Philadelphia and New York City. Before leaving USA, Elder Unruh, along with several of the other delegates, had a private meeting with President Ulysses S. Grant who pointed out that the US Constitution guarantees religious freedom for all Americans. However, President Grant did warn the delegates on a few points. While the president thought it would be unlikely the Mennonites would be pressed into military duty, he refused to rule it out entirely. Also the case was established that American law would not provide the Mennonites the autonomy to “self-govern” themselves [64].

Elder Unruh came away from the delegation trip favoring Dakota as a place for the new home for the Low German Mennonites of Volhynia. He felt the land was good for both crops and livestock and he stated that they need not look nor wish for better land[65]. Legend has it that the delegates then ran into Daniel Unruh in New York City. Daniel Unruh was a Mennonite leader from Crimea who was a bit ahead of the script. He, with a group of Mennonites from Crimea, was already arriving in USA, having left Russia for good. This Daniel Unruh would become the first Mennonite settler in Dakota[66].

Upon his return home, Elder Unruh encouraged his people to begin making preparations for a move to America. The Elder made numerous appeals for aid to North American Mennonites on behalf of his congregants. The biggest hurdle the Volhynians had was financial. Since the Volhynians were so poor, Unruh requested loans in the amount of $40,000[67] from American Mennonites in places like Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, and Ontario to aid the Volhynians’ emigration. That’s the equivalent of slightly more than $900,000 today[68]. Unruh’s appeals for aid were answered by American Mennonites and enough funds were raised to pay for most of the Volhynians’ passage to America.

At this time the population of Low German Mennonites in Volyn Gubernia was just short of 2,500 people. In 1874, almost 1,500 of these expressed their wish to leave Russia. The population of the three biggest villages was Karolswalde, 750; Heinrichsdorf, 150; and Antonowka, 536. All of these folks wished to leave Russia except for 506 who wished to stay[69]. According to subsequent estimates, about 600 Low Germans actually did stay in Volhynia beyond 1874[70].

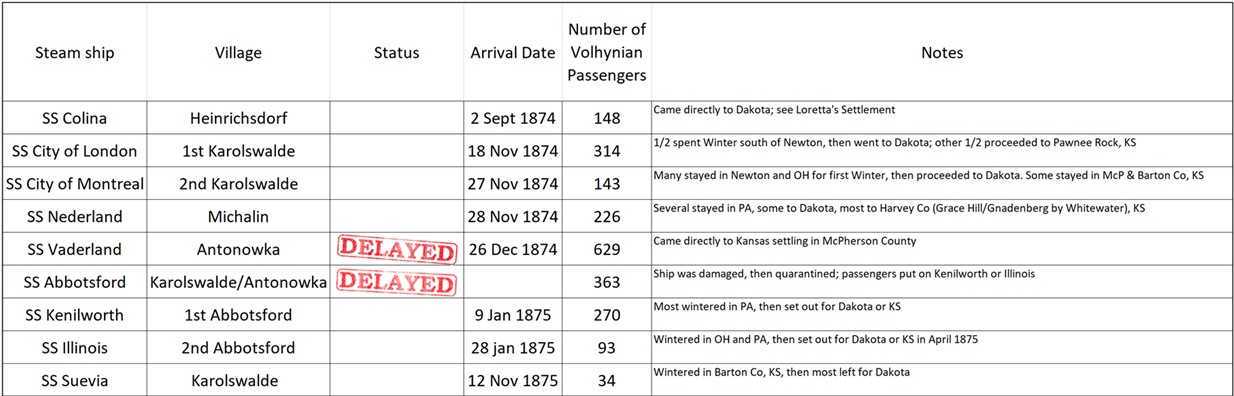

The great majority of the Low German Volhynian Mennonites left Europe aboard the following seven ships. It’s significant that just over half of these passengers suffered various types of travel delays.

- The SS Colina, carrying a great number of the Heinrichsdorf villagers, was the first to reach North America. It landed in New York City in early September, 1874, and these folks came straight to Dakota and would establish the Loretta Settlement south of Avon.

- Next were the SS City of London and the SS City of Montreal, together carrying 457 Karolswalde villagers. These two ships arrived in New York in the second half of November. Some of these folks wintered with Mennonite families in PA and OH but most continued on to Newton, KS. In the spring of 1875 about half of these proceeded on to Dakota while the other half moved and settled at Pawnee Rock in Barton Co, KS. A small number stayed in McPherson County, KS.

- The next ship was the SS Nederland which carried the majority of the Michalin villagers. This ship arrived in Philadelphia in late November and the majority of the passengers came to Kansas, settling near Whitewater.

- Next came the SS Vaderland. This was the single largest load of Volhynians – 629 almost all from Antonowka. This ship suffered mechanical problems en route across the Atlantic and was late arriving to Philadelphia. When it got there, the passengers insisted on continuing on to Kansas immediately, even though it was Winter by then. No arrangements had been made for their arrival in Kansas so when they got there, amid an historically cold snap of weather, they had to be housed in a vacant warehouse until Spring. After a smallpox epidemic swept through the warehouse, perhaps around 200 died and were buried in a mass grave in Florence, KS. These folks formed the basis for the group known as the Lone Tree folks in Kansas.

- The next group was the SS Abbotsford, which included Elder Tobias Unruh himself. The Abbotsford actually collided with another ship in the English Channel and had to return to Liverpool for repairs. 3/4ths of the passengers were loaded aboard a ship called the SS Kenilworth, which then arrived in Philadelphia in early January. The remaining quarter waited aboard the Abbotsford, only to have smallpox break out and the ship subsequently quarantined. The Abbotsford then collided with a second ship so it was forced to be abandoned altogether. The remaining passengers, including Elder Unruh, were put on the SS Illinois and finally arrived in Philadelphia in late January 1875 – about a month late. Most of the passengers from the Kenilworth and the Illinois stayed in Pennsylvania or Ohio for the winter and then moved on west in the Spring of 1875 – about half coming to Kansas and half to Dakota.

- Finally, the SS Suevia, carrying a relatively small group of Karolswalde villagers, arrived in New York in November, 1875. These wintered in Kansas and then most moved on to Dakota[71].

When they reached New York City or Philadelphia, these Low German Mennonites had to make a decision about their destination in the United States. In those days, immigrants were met at the docks by many different folks trying to sell them land. Land grant railways were among the most aggressive dealers and they really wanted good farmers – like the Mennonites – to buy their land. Unfortunately, the Volhynians had to make these decisions without Elder Unruh’s guidance since his ship had been so severely delayed. In Kansas, railroad companies had been granted land from the government and now they were looking to sell this land to immigrants. The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad very badly wanted to sell its land in central Kansas to any Mennonites. The Santa Fe had a German-speaking land agent and offered substantial benefits. The Santa Fe also had the trust of the Mennonite Board of Guardians (the American Mennonite body helping to place the emigrants in the new country)[72]. Before the Low German Volhynians arrived in USA the Swiss Volhynians and the very large Alexanderwohl group had already come to Kansas[73].

In Dakota, the Territorial Immigration Commission took the lead in negotiating to bring immigrants to the area[74]. Remember that one of the very first Low German Mennonite immigrants, Daniel Unruh, settled in Dakota already in 1873. Further, Elder Tobias Unruh, as well as some of the Swiss Volhynians, clearly favored Dakota as a new home. But the Volhynians were largely left on their own to make a decision about their final destination. It must have been a very confusing and daunting process for these penniless immigrants. In the end, almost 70% of them decided to settle in Kansas[75].

Elder Unruh himself spent the remaining months of the Winter of 1875 in Pennsylvania, and then set out for Dakota in April of 1875. He settled with his family in the northwest corner of Turner County, near Silver Lake. He only lived in Dakota for a few months, though. After suffering for a couple weeks with typhoid fever, he died on 24 July and was buried at the Schartner Mennonite Cemetery east of Silver Lake[76].

The Volhynians in Kansas really did not fare very well in the early years. They were very poor and the trip to America had placed them all in debt to American Mennonites who had funded their journey. In Kansas, they were left under the care of Alexanderwohl leaders who, quite frankly, treated them in a very condescending manner. The Volhynians were seen as lazy; they didn’t know how to farm well; and their Mennonite religious standards were not up to levels seen as acceptable by Alexanderwohl and other General Conference leaders[77]. The Volhynians quickly became disenfranchised. Within three years John Holdeman’s movement began in Central Kansas and the majority of the Volhynians there moved away from the General Conference Mennonite Church and joined Holdeman[78]. The argument has been made that these Volhynians would not have left the General Conference if Elder Tobias Unruh had just come to Kansas.

The Low German Volhynians had a Hard Road. These folks moved into Volyn Gubernia, largely from Przechowka-associated communities in the Prussias and Poland around the turn of the 19th Century. Low German Mennonites moving into Volhynia struggled with the requirement of paying rent for land which was not necessarily fertile. Their daily lives included interaction with many different ethnic groups and their own

culture and religious vibrancy were adversely affected. Upon immigrating to North America, two of the seven ships suffered misfortunes which caused delays and separated the people from their leaders. They soon discovered that, due to poverty and isolation in Volhynia, their culture had developed in a very different way to other Russian Mennonites in USA. As a result, many of them who settled in Kansas left the General Conference Mennonite Church.

But those who stayed behind in Russia suffered unthinkable hardships. Perhaps around 600 Mennonites stayed back in Volhynia after 1874. We’ve been able to identify almost 400 Mennonites leaving Volyn after that year, and perhaps by the early 19-teens, less than a dozen Mennonites remained there[79]. Two who did stay, Benjamin J. Nachtigal and Ernst Koehn, suffered tremendous adversity. In April, 1936, the Peoples Commissariat of Ukraine issued Resolution number 776-120ss which forcibly evicted Germans from their homes in Volhynia. In the summer of 1936 as many as 45,000 Germans were loaded into cattle cars and shipped by rail almost 2,000 miles east to Kazakhstan[80]. The Benjamin Nachtigals and Ernst Koehns were among these. The Nachtigals were imprisoned in Jezkazgan, Kazakhstan, and some family members remain there to this day. The Koehn family’s story is unknown but Ernst’s son Leonard actually made his way back to Antonowka and was still living there in the very early 2000s[81].

During the first few decades following the 1874-5 migrations, Elder Tobias A. Unruh was the subject of criticisms from Mennonites from Kansas and Pennsylvania who sometimes claimed that he deserted his people. Since more than 70% of the Low Germans from Volhynia settled in Kansas and only a minority came to Dakota the argument was been made that he was negligent going to Dakota instead of Kansas.

Of course, we cannot tell what Elder Unruh’s plans were for his congregation but he personally quite clearly favored Dakota as a place for a new home in USA. The fact that travel delays separated him from the bulk of his people was a factor that was beyond his control. He may very well have thought that, with so many other Mennonite leaders already in Central Kansas, his guidance would be needed more in Dakota. He also may very well have expected that ministers from Volhynia like Andreas Eck and Samuel Koehn who were already in Kansas, would lend support[82]. However, these ministers unfortunately shrugged leadership responsibilities.

Any criticisms directed at Elder Tobias Unruh for settling in Dakota are massively unfair and were made without the advantage of historical perspective. Of course, today we can see that Elder Unruh set the wheels in motion for the Volhynians’ emigration to USA. He went on the 1873 delegation and made vital contributions for the preparation of his people to come to North America in helping to secure funding for the Volhynians’ passage across the Atlantic.

In addition to his leadership during the migration, Elder Unruh made important contributions to Low German Volhynian history in that he kept very important records. First is the Karolswalde Churchbook. Unfortunately, this book became lost in the very early years of the 20th Century. The record would presumably list the histories of all the Low German Volhynian congregants. At this time, the whereabouts of the original is unknown[83].

Elder Unruh also kept his own baptism register which covers baptisms performed from 1853 until the emigration of 1874. It also includes some notes on the early years in Dakota, as well as some subsequent baptisms. This perhaps is the single most important document available for the history of the Volhynian Low German Mennonites. The original book is located at the Heritage Hall Museum and Archives in Freeman, South Dakota, and my photos of it and the edited version of the Martha Becker translation are available in the Volhynia section at www.mennonitegenealogy.com[84].

Finally, Elder Unruh also kept diaries of his trips to America. These diaries are invaluable records which document Atlantic travel in the late 19th Century and give insight into the mind of a Low German Mennonite leader of the time.

The Low German Volhynians did have a tough emigration experience and those who arrived in Kansas, separated from Elder Tobias Unruh, did indeed go through some hard times. But due to Elder Unruh’s efforts to guide their immigration process they were removed from a Russian province which would soon undergo revolution and war. Due to Elder Unruh’s efforts the great majority of the Low German Volhynians avoided the horrors of 20th Century Ukraine- including the Russian Civil War, collectivization, de-kulakization, the deportations of 1936 (as well as others), as well as World Wars I and II.

[1] Of course, this is just a family legend and cannot be proven. In years of study I have found several Mennonite immigrants who left Lilewa after Andreas Ratzlaff. I’ve also found a handful who, evidence suggests, never left Russia at all, staying in various parts of the empire even after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

[2] Menno Simons (1496-1561).

[3] Schapansky, Henry, The Mennonite Migrations (and The Old Colony, Russia), Country Graphics & Printing Ltd., Rosenort, Manitoba, Canada, 2006. See Chapters 1-3. Royal and Ducal Prussia may be more commonly known, today, as West and East Prussia, respectively. Mennonite settlements in the Vistula Delta, specifically at Danzig, were certainly established by 1550. Other settlements in the Vistula Valley, like Montau or Obernessau, could have also originated as early as the mid-16th Century.

[4] The 14 congregations or gemeinden in Royal Prussia were: Ladekop, Danzig, Elbing, Bärwalde, Thiensdorf, Rosenort, Orlofferfelde, Heubuden, Tragheimerweide, Schönsee, Montau, Przechowka, Obernessau, Tiegenhagen. This does not include congregations in Ducal Prussia, Masovia, or Brandenburg, or daughter congregations.

[5] Schapansky, The Mennonite Migrations, Chapter 4. The Kingdom of Poland’s economy peaked already in the early 17th Century due in part to Mennonite grain production.

[6] The Flemish tended to cling more to the Dutch language while the Frisian tended to cling more to High German. The use of these languages was because the scriptures had not been translated into Low German. However, Low German was a very old language even used as a trading language by the Hanseatic League in the 14th and 15th Centuries. The myth that Low German exists only as a spoken and not a written language is simply untrue.

[7] Flemish congregations included Danzig, Heubuden, Elbing, Barwalde, Ladekop, Rosenort, Tiegenhagen, Przechowka; Frisian congregations included Danzig, Orlofferfelde, Thiensdorf (Elbing), Montau, Schonsee, Obernessau, Tragheimerweide.

[8] Allied with Jan Luies and Uco Walles and Groningen in the Dutch Lowlands.

[9] Other villages included Konopat, Dworzisko, Christfelde, Kosowo, Dorposch, Jamerau, Glugowka, Ausmas, Beckersitz, Ostrow Kampe as well as a couple others.

[10] Many villagers from Jeziorka and the Neumark villages can be found listed in the Przechowka church records. The other daughter settlements include die kleine Schule in Schönsee and Wymysle by Gombin.

[11] Additional names include as found in the Przechowka Church records. See “Przechowka Church Records”,

originally translated by Jacob A. Duerksen, Velda Richert-Duerksen, and the Mennonite Immigrant Historical Foundation staff in Goessel, KS; transcribed and edited by Rod Ratzlaff.

[12] Chortitza was founded in 1789; Molotschna was founded in 1804. Krahn, Cornelius and Walter W. Sawatsky. "Russia." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. February 2011. Web. 7 Nov 2019.

[13] Отримано з https://uk.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Волинська_губернія&oldid=26419406. Volyn Gubernia (Волинська губе́рнія) covered an area of just over 27,742 square miles. Ostrog County (Острожский уезд or повіт) covered an area of 1,184 square miles. For comparison’s sake, the State of Iowa is a little more than twice the size of Volyn Gubernia. Ostrog County was about double the size of Harvey County, KS, or Bon Homme County, SD.

[14] Travel in the area was difficult; for an example see “The German Baptist Movement in Volhynia” by Donald N. Miller. Ostrog was difficult to reach via river simply because of geography. Volhynia, and Ostrog, is bounded on the west, south, and east, by highlands and therefore the rivers flow to the north. For instance, to reach large cities of Odessa or Kiev by river one needed to go far to the north, to the Pripyat, then to the Dnieper, then south. As the crow flies, Odessa was some 328 miles from Ostrog. However, to reach Odessa from Ostrog via river, one would have to travel almost 900 miles. Railroads were not introduced to the area until the early 1870s.

[15] Valery Kovalchuk, Yury Korzun “The situation of national minorities Zaslavschyny early 20th years of XX century”, http://www.myslenedrevo.com.ua/uk/Sci/Local/Zaslav/Empires/AdminDivision.html; The First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897; Breakdown of Population by Mother Tongue and Districts in 50 Governorates of European Russia; 1897.

[16] Волынская губерния”, Brokgauza and Efrona Encyclopedic Dictionary, St. Petersburg/Leipzig, 1907 edition.

[17] For instance, the Mennonite village of Fürstendorf: It appears as if it was first known as Nikitska, or the Nikitska Tract (Военно-Топографическая Карта Волыской Губерний 1855-1877; see Plate XXII), then the Mennonites moved into the village naming it Fürstendorf. After the 1860s it became known as Lilewa or Leeleva but then German Lutherans again called it Fuürstendorf after the 1870s (“Kirchspiele in den Gouvernements

Wolhynien, Podolien und Kiew 1909”; https://wolhynien.de/pdf/1909Pingoud_Tab.pdf). After the Bolshevik Revolution it can be found listed as Lesnaya, then later, Lesna. After the fall of the USSR, it’s found by its modern Ukrainian name, Lisna.

[18] The First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897.

[19] It’s important to remember that the Mennonies of Volhynia did not live among many Russians. Rather, they lived among Ukrainians. Ukrainians and Russians are two separate and distinct groups of people with different languages, traditions, and customs. During the 19th Century, Russia occupied Ukraine, and did everything it could to squash Ukrainian culture.

[20] Witness the Polish insurrections of the mid-19th Century, various pogroms, etc. For more examples see Valentyna Nadolska, “Volyn Within the Russian Empire: Migratory Processes and Cultural Interaction” or Finkel, Gehlbach, and Olsen, “Imperfect Institutional Change: Peasant Disturbances Before and After Russia’s Emancipation Reform of 1861”, August 2011.

[21] Administratively, Michalin was located in Bratslav Voivodeship, then Bratslav Namestnichestvo (Брацлавское наместничество) until 1796 when administrative lines were redrawn and the village was then in Kiev Gubernia (Киевская губерния, Казатинская волость), it was never in Volyn Gubernia.

[22] Hiebert, Clarence, The Holdeman People: A Study of the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, 1858-1969, Case Western Reserve University, Ph.D., 1971, p 101. These Old Flemish from Michalin likely moved on to establish Karolswalde. With new evidence being found right now, it appears almost certain that Old Flemish villagers from Michalin established Karolswalde.

[23] Many Michalin settlers came from villages of the Montau Gemeinde, primarily Treul. See “Deutsch-Michalin Mennonites” by Adalbert Goertz.

[24] Others included Bartel, Unruh, Balzer, Isaac, and Penner. See Adalbert Goertz above, as well as Grandma's Window, V 5.4r2; Kenneth L. Ratzlaff, Lawrence, Kansas, 11/2000 - 7/2019; California Mennonite Historical Society Genealogy Database Project.

[25] Villages with Low German inhabitants included these, as well as Bereza, Dosidorf, Horodyszcze, Lindental, Melanienwald, and Waldheim. Wolla appears to have been located near Rafaelovka on the northern Styr River but we don’t know its exact location (Boese, J.A., The Prussian-Polish Mennonites settling in South Dakota, Pine Hill Press, 1967, p 34). This Wolla is certainly a different village to Wola Wodzinsky near Warsaw. Some of these villages, such as Horodyszcze and Dosidorf were homes to both Low German as well as Swiss Mennonites.

[26] “Mennonite Immigration from Jeziorka, West Prussia to Volhynia, Russia in 1803 and 1804” compiled by Glenn Penner; “Antonovka Land Contract, 1804”, translated from the Russian by Ola Heska, edited by Rod Ratzlaff; “30 Sept 1819, List of Mennonite Families Residing in Villages…”, and “Contract Between Count Jablonowsky and Mennonites”, St. Petersburg Archives Reel 8, Fond 383, Opis 29, Delo 1212, Request 155, Documents 33, 37, 38,

39; Kostiuk, Michal, German Colonies in Volhynia (XIX-XX Centuries), Ternopil, 2003, p 64.

[27] Schrag, Martin H. "Volhynia (Ukraine)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1959. Web. 6 Nov 2019.

[28] “Elder Tobias Unruh Baptism Register: 1854-1889”, transcribed by Martha Becker, edited by Rod Ratzlaff. Names found in the register include the following, listed here from most to least commonly found: Unruh, Jantz, Schmidt, Koehn, Boese, Becker, Wedel, Dircks, Schultz, Buller, Nachtigal, Voth, Ratzlaff, Decker, Eck, Ewert, Siebert, Nickel, Funk, Penner, Schartner, Richert, Rudiger, Litke, Thomas, Baier, Frey, Isaac, Priess, Tesmer, Block, Teske, Timmer. For a listing of Frisian and Flemish Mennonite names see Schapansky, The Mennonite Migrations, p80-87.

[29] Schrag, Martin H. "Volhynia (Ukraine)."; “Waldheim, Molotschna and Heinrichsdorf, Volhynia

1833-1851”, Glenn Penner and Steve Fast. Heinrichsdorf was located immediately southeast from the Ukrainian village of Velyki Korovyntsi, about 13 miles northwest from Berdychiv or 80 miles southeast from Karolswalde. In 1906 Heinrichsdorf was, administratively, located in Zhytomyr County (повіт or уезд), Ozadovka Township (волость). In 1906 the village was listed as Henrietovka (Генріетовка) (Списокъ Населенныыхъ Местъ Волынской Губерний, Житомиръ, Волынская Губерная Тинография, 1906.).

[30] “Compilation of Mennonite Villages in Russia”, Tim Janzen, 2004.

[31] “1858 Census Extracts for the Karolswalde, Volhynia Mennonites Who Settled in Jadwinin, Volhynia in 1858 Zhitomir State Archives, Fond 58, Opis 1, Delo 1099”, originally translated from the Russian by Ola Hosk for Glenn Penner.

[32] “Compilation of Mennonite Villages in Russia”, Tim Janzen, 2004. Regarding the founding of the village of Fürstendorf, at this time my own personal belief is that the village was founded by villagers returning to Antonowka area from Dosidorf in 1868. See letter written by Elder Tobias A. Unruh in “Der Mennonitischer Friedensbote”, March 15, 1874, p 43, quoted in full in, Hiebert, Clarence, The Holdeman People, p 108. Elder Unruh mentions a group of his Antonowka-associated congregants who have recently (1874) left the village to move into the forest. Could this also mean the village of Menziliski?

[33] Menziliski is commonly overlooked but, for instance, we can see it listed in “Elder Tobias Unruh Baptism Register: 1854-1889” as well as family histories such as Schneider, Marie Ratzloff, History of Grandfather Jacob J Ratzlaff and Descendants, 1958, page 120. In addition to the villages listed above, Tobias Unruh also had congregants living in “Nowamalin Walde” which would indicate a settlement in the forest south of Novomalyn, north of the Viliya River perhaps north of Antonowka or Kuniv. Additionally, after 1874 the villages of Mykhailivka and Stanislavka were also settled “History of the German Colony in Mykhailivka Izyaslavschyni”, Romanchuk A., 2003; P47 S43 (alt. A47 B43) “Ostróg” (1:100 000 WIG - Mapa Taktyczna Polski), Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny, Warszawa, 1921; also see Списокъ Населенныыхъ Местъ Волынской Губерний, Житомиръ, Волынская Губерная Тинография, 1906. After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 many remaining Germans were relocated to a village about 4.25 miles almost due south of Pluzhne called Yuvkivtsi, where they displaced a local Muslim population. The Germans named this village Zonental (“History of the German Colony in Mykhailivka Izyaslavschyni”).

[34] See: Ostroh at “https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ostroh&oldid=921862995” and Mezhyrich at https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Mezhyrich&oldid=903658508.

[35] “The German Migration to the East”, Jerry Frank, Spring/Summer 1999 FEEFHS Journal Vol. 7, #1 and 2.

[36] Marchlewski, Wojciech, “Different Neighbours”; Hauländer, en.wikipedia.org; 2017.; Frank, Jerry, “The German Migration to the East”. One may see usage of the term Hollander in “Antonovka Land Contract, 1804”. One may find the term spelled in a number of different ways including Hauländer in German, Olęder in Polish, Галендры in Russian.

[37] An example is the “Land Contract for Mennonite Colonists Resettling in the Village of Dosidorf, 1848”, translated from the German by Ute Brandenburg and edited by Rod Ratzlaff. This is a contract for Low German families from Antonowka moving to and settling at the village of Dosidorf. The terms of the land contract stipulate that the eight Low German families would lease the land from landowner Christian Moses Goering, for a term of twenty years.

[38] Many Volhynian anecdotal histories indicate that villagers came directly from “Holland” to Volhynia. Examples include Volhynian Ratzlaff and Schmidt records.

[39] These types of houses can still be found in areas of Mennonite settlements in Poland. See also: Krause, Claire Schachinger “A Brief History of Karlswalde – A German Village in Russia” Lebanon Historical Society February 2, 1977; Miller, Donald N., “The German Baptist Movement in Volhynia”, 2008.

[40] Witness statements by Marie Ratzlaff Penner.

[41] Unruh, Jacob, “From Village Life to Kansas Plains”, 1978; Janz, Jacob B, “Mennonite Life in Volhynia, 1800-1874”.

[42] For instance, “Antonovka Land Contract, 1804”; Giesinger, Adam, “A Volhynian German Contract”; “Landenteignungsliste, Lessnaja/Fürstendorf Ujesd Ostrog, Wolost Plushno”, wolhynien.de, 2016.

[43] Janz, Jacob B, “Mennonite Life in Volhynia, 1800-1874”, pp7, 8; Hiebert, Clarence, The Holdeman People p108.

[44] “Острог, уездный город Волынской губернии”, Brokgauza and Efrona Encyclopedic Dictionary, St. Petersburg/Leipzig, 1907 edition.

[45] Janz, Jacob B, “Mennonite Life in Volhynia, 1800-1874”, p 7.

[46] Janz, Jacob B, “Mennonite Life in Volhynia, 1800-1874”, p 8; Unruh, Jacob, “From Village Life to Kansas Plains”. Jacob Ratzlaff, 1893 SS Polaria shiplist; Andreas J Ratzlaff passport from my personal collection.

[47] Janz, Jacob B, “Mennonite Life”, p 8.; Unruh, Velma Penner, “Leeleva Village”. See also Forests and Forestry in Poland, Lithuania, The Ukraine, and the Baltic Provinces of Russia, compiled by John Croumbie Brown, LL.D., Edinburgh, 1885.

[48] “Острог, уездный город Волынской губернии”, Brokgauza and Efrona Encyclopedic Dictionary, St. Petersburg/Leipzig, 1907 edition.

[49] Various articles at http://istvolyn.info/index.php; Романчук О.; Romanchuck, Alexander [Романчук О.], ‘Velbivnomu Miners” [Були у Вельбівному шахтарі], 2012.; Romanchuck, Alexander [Романчук О.], “Bilotyn Village's Past and Present” [Село Білотин в минулому і сьогоденні], 2012.; Romanchuck, Alexander [Романчук О.], “Górnik -The Village of Kam’yanka on Izyaslavschyni “ [«Гурнікі» села Кам’янка на Ізяславщині], 2012.; Romanchuck, Alexander, and Medlyarska, Sofia [Олександр Романчук, Софія Медлярська], “History of the Czech Colony Yadvonino; Ostrozhskogo County” Zaslavschyna in the late 19th and Early 20th Centuries [З історії чеської колонії Ядвоніно Острозького повіту][ Заславщина від кінця XVIII до початку 90-их років ХХ століття], 2011.; Vykhovanetsʹ, T.V. [Вихованець Т.В.], “The History of the Princes Kryvynskoyi Yablonovska” [До історії Кривинської резиденції князів Яблоновських], 2012.

[50] Janz, Jacob B, “Mennonite Life in Volhynia, 1800-1874” pp 7, 8; Hiebert, Clarence, The Holdeman People, pp101, 107.

[51] For instance, John B. Unruh (1885-1971) worked at the tavern or inn in Antonowka before coming to America in 1906.

[52] Janz, Jacob B, “Mennonite Life”, p8.

[53] Hiebert, Clarence, The Holdeman People, p96, 125, 128, 135-139; Haury, David A., Prairie People: A History of the Western District Conference, Faith and Life Press, Newton, KS, 1981, p 41-51.

[54] Of course, not all the residents at Chortita or Molotschna were wealthy. Quite the contrary, there did exist a problem with a good number of people being landless. However, generally speaking, the situation of the Low German Mennonites in Volhynia was a good deal worse than that of Chortitza or Molotschna residents.

[55] For instance, see Friesen, Peter M., The Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia (1789-1910), translated from the German; translation and editorial committee: J. B. Toews, Abraham Friesen, Peter J. Klassen, Harry Loewen. Fresno, Calif.: Board of Christian Literature, General Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches, 1978. [Friesen’s history was originally published in 1911].

[56] Krahn, Cornelius and Richard D. Thiessen. "Schartner, Johann (1827-1912)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. November 2006. Web. 7 Feb 2017; Friesen, Peter M., The Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia (1789-1910).

[57] Schrag, Martin H. "Volhynia (Ukraine)".

[58] Hiebert, Clarence, The Holdeman People: A Study of the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, 1858-1969, Case Western Reserve University, Ph.D., 1971, p 108.

[59] Schmidt, John F. "Michalin Mennonite Church (Volyn Oblast, Ukraine)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1957. Web. 6 Nov 2019.

[60] “Elder Tobias Unruh Baptism Register: 1854-1889”.

[61] Kostiuk, Michael, German Colonies in Volhynia (XIX - XX centuries), Ternopil, 2003. pp 43-52, 77, 95-96, 139, 201-02; Smith, C. Henry (1981). Smith's Story of the Mennonites. Newton, Kansas: Faith and Life Press.

[62] Списокъ Населенныыхъ Местъ Волынской Губерний, Житомиръ, Волынская Губерная Тинография, 1906.

[63] The Delegation of 12 included Leonhard Suderman and Jacob Buller from Alexanderwohl (Molotschna), Tobias Unruh from Volhynia, Andreas Schrag of the Swiss Volhynians, Heinrich Wiebe, Jacob Peters, and Cornelius Buhr from the Bergthal Colony, William Ewert from West Prussia, Cornelius Toews and David Klassen of the Kleine Gemeinde, Paul and Lorenz Tschetter of the Hutterites. Tobias Unruh traveled with Ewert, Suderman, Buller, and Schrag, aboard the SS Frisia which arrived in New York City on 29 May 1873.

[64] “The Diaries of Tobias A. Unruh Diary”, 8 August, 1873, translated by Abe J Unruh.

[65] Ibid., 21 June, 1873.

[66] The meeting at Castle Garden at New York City between the Delegates and Daniel Unruh from Crimea is legendary. However, Daniel Unruh did indeed travel to USA aboard the SS Hammonia which landed at Castle Garden on 15 August, 1873. According to his diaries, Elder Tobias Unruh, along with the Tschetter brothers, boarded their ship for their return to Europe on 14 August, 1873. Could they have met or did they miss each another by one day? For more information about Daniel Unruh see “Daniel Unruh and the Mennonite Settlement in Dakota Territory” John D Unruh and John D Unruh Jr, Plett Foundation, https://www.plettfoundation.org/articles/daniel-unruh-and-the-mennonite-settlement-in-dakota-territory/

[67] Hiebert, Clarence, The Holdeman People, p 107.

[68] Per U.S. Dollar Inflation Calculator at http://www.in2013dollars.com/. By similar extrapolation, a ticket on a steamer across the Atlantic in steerage class cost about $30 in 1874 (Nadell, Pamela Susan, “The Journey to America by Steam: The Jews of Eastern Europe in Transition” Ohio State University, 1982, p 88). The $40,000 requested by Tobias Unruh would have purchased him slightly more than 1,300 steerage tickets.

[69] “Mennonites in Volyn Gubernia”; 1874; St. Petersburg Archives, Fond1246 Opis 1 Delo 8 Page 137.

[70] “Thiesen, John D., “Mennonite Ship List; “Mennonites in Volyn Gubernia”; 1874; St. Petersburg Archives.

[71] Thiesen, John D., “Mennonite Ship Lists 1872 – 1904” (J. Hubert, J. Thiesen); Copyright 1995; Unruh, Abe J., The Helpless Poles, Pine Hill Press, Inc, 1973, Chapter VIII; Boese, J.A., The Prussian-Polish Mennonites, p 68-70; See also Boese, J.A., Loretta’s Settlement, Tyndall, S.D., 1950.

[72] Bender, Harold S. "Mennonite Board of Guardians." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1957. Web. 6 Nov 2019.

[73] For an excellent analysis of the Alexanderwohl group’s experience in Nebraska and Kansas, see John D Unruh, Jr, “The Burlington and Missouri River Railroad Brings the Mennonites to Nebraska, 1873 – 1878, [Part II], Nebraska History 45 (1964): 177 – 206. For information concerning the Swiss Volhynians’ immigration experience see Schrag, Martin, The European History of the Swiss Mennonites from Volhynia, Swiss Mennonite Cultural and Historical Association, Mennonite Press, Newton, KS, 1974, pp 81, 82.

[74] “Come to God's Country: Promotional Efforts in Dakota Territory, 1861-1889” Kenneth M. Hammer, South Dakota State Historical Society, 1980; Hohansen, J. P., "Immigrant Settlements and Social Organization in South Dakota" (1937). Bulletins. Paper 313; Unruh and Unruh, Daniel Unruh and the Mennonite Settlement in Dakota Territory”.

[75] Unruh, Abe J., The Helpless Poles, Chapter VIII.

[76] “Tobias Andreas Unruh, #70741”, Grandma's Window, V 5.4r2.

[77] Haury, David A., Prairie People, pp 41-51.

[78] See: Hiebert, Clarence, The Holdeman People, pp 130-131.

[79] Friesen, Peter M., The Mennonite Brotherhood, p 870.

[80] Pohl, J. Otto, “The Deportation and Destruction of the German Minority in the USSR”, 2001.

[81] Personal interviews with Ludmila Nachtigal Heitz, granddaughter to Benjamin J Nachtigal; Personal interview with Shane Kane and Stanley Wiggers, both of whom have met Leonid Koehn in Antonowka and photographed him and his father’s baptism documents.

[82] Haury, David A., Prairie People, p 50

[83] See Thiesen, John D., “Karolswalde Church Book Notes”, 23 Oct 2008.

[84] “Elder Tobias Unruh Baptism Register: 1854-1889”, transcribed by Martha Becker, edited by Rod Ratzlaff.

A note regarding the spelling of village names: We in 21St Century USA get too hung up with the spelling of the names of historic European villages and other places. We have to remember that spellings have changed over time and when a people of one language took over ruling an area from people of a different language, they would spell names differently. Areas in Volhynia were ruled by Poles and Russians and Germans, while the areas themselves were Ukrainian. Also, there were many Jewish inhabitants of the area. Therefore, for Volhynian villages, we will find place names in Polish, Russian, German, Ukrainian, and Yiddish. Also, we have to remember that these names were many times spelled phonetically by people living there. You’ll find many different spellings for the same village; don’t become overly concerned.

TOBIAS A. UNRUH AND THE LOW GERMAN MENNONITES OF VOLHYNIA

© Rodney D. Ratzlaff, Freeman, South Dakota, November, 2019.